The problems of running a sleigh!

With six months of night and of day,

To deliver a toy

Or in Hawaii, some poi,

I don’t send the elves out to play.

Synopsis: I’m a family practitioner from Sioux City, Iowa, transitioning my career. While my one-year non-compete clause ticks out I’m doing locum tenens work, and having adventures. Currently I’m in southeast Iowa. I played Santa this week, and my sense of humor broke loose.

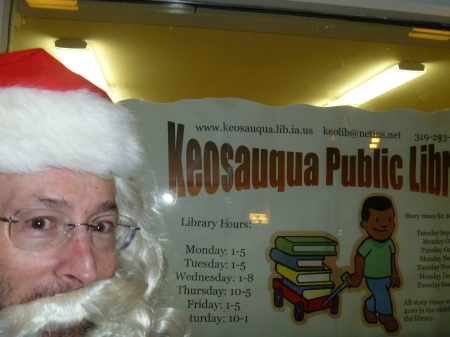

I put on a red suit and went to the Keosauqua Public Library as Santa.

I talked with one of the librarians after the rush of kids slowed down.

He commented he hadn’t seen my sleigh.

“It’s second shotgun season,” I said. “You know, I was crossing the Van Buren County line just before dark, keeping the sleigh low along the river over there by Bonaparte, I heard a shot and I’m darned if a 12-gauge slug didn’t crease Donner’s left hind hoof. Scared the heck out of me. I took her up about two hundred feet, swung south there and crossed into Missouri, set her down in an alfalfa field to check out the damage, wouldn’t you know up drove a guy, a doc, in a ’98 Toyota Avalon. We yacked a little bit, he said he’d do what he could for Donner even if he weren’t a vet, and let me drive his car into town. That’s why I came in late.”

The librarian nodded.

“Heck of a deal,” I said, “You know at the North Pole we get six months of daylight to make all those toys but when the sun goes down on September 22, it goes down and it stays down, and I’ll tell you what, it gets dark. And we just keep working through the winter solstice, it gets to be December 24th and I head south, I cover a lot of ground. You know, I remember back winter of ’93 when we had all that snow, I was fixing to land on the roof of a farmhouse outside of Effingham, Illinois. Well, they hadn’t shoveled the snow off the roof and wouldn’t you know, the thing caved in and I put the sleigh down in the farmyard about the time the family came running out of the house. Everyone was OK and I gave out the presents one on one and when I turned back to get in the sleigh, well, you know how the Santa’s breed of reindeer makes AGH?”

He furrowed his forehead at me.

“Anti-Gravity Hormone,” I said. “Well, those animals got awful hungry with the cold and the snow and all and they smelled some of those apples still at the top of the apple trees there around the farmyard and, well, you just can’t trust those reindeer with your back turned. Except maybe Prancer, and even him…

“So I turned around and those reindeer were browsing on the twigs at the top of the tree, getting the mummy apples, they were going at it pretty good and wouldn’t you know I had to borrow a ladder to get back in the sleigh, and climbing that thing isn’t easy when you’re as short and fat as I am, it’s not like you can just put your finger on one side of your nose and whoosh you’re up like you can in a chimney.

“That was the year I got a letter from a fellow in the jail in Lame Deer, Montana, on the Northern Cheyenne reservation. What he wanted, see, what he wanted was lithium. I had checked my list on this guy, twice, and I can tell you he hadn’t been good. Really, pretty naughty. But I looked at what he wanted, and, you know, I figured, lithium. You know, why not. Ever since then someone asks for lithium, I don’t even check the list, I just figure I’ll make the stop. And it’s a simple package, doesn’t weigh much, not like those cotton-pickin’ ponies. Doesn’t take hardly any elf labor.

“Me and the reindeer we get back from a run and we’re really, really tired. So are the elves, so is Mrs. Claus. But we get the animals out of the harness, and even if the elves are getting sleepy I get ‘em to hang up the harness, we don’t use saddle soap anymore…”

“No?” he asked

“No, we went to all-Kevlar harness, oh, heck, it’s got to be twenty-five years ago. Just saves one more step when I bring in the sleigh. Takes twenty-four elves to curry-comb the reindeer and they’re getting a little edgy at that point in the season. If they haven’t mucked out the reindeer stables, well, I got to get on ‘em about that, oh, I’d say three years out of four. But me? I’m the one that feeds ‘em. You know, we got some really first class hay out of Montana last year, good clean alfalfa. Not like that, you know, Santa shouldn’t use such language, so I’ll just say stuff with a capital SH that we were getting out of Siberia. Tell you what, don’t sign a contract with a Chechen. I should have known better than to deal with a company’s got everyone on the naughty list.

“By the time the reindeer are taken care of and stabled, we sit down to darned fine meal. You know those dry does in the reindeer herd, I’ll tell you what we eat pretty darn good. Then we go take a nap. Now, remember it’s the Arctic night, and we just snooze for a couple of months. When we get up Mrs. Claus keeps making breakfast, coffee, doughnuts, reindeer salami and cold storage eggs, till the sun comes up on March 23, and then we’re back at it. Magic reindeer drop their antlers when the sun comes up like that, that’s when they stop making AGH and they don’t fly till they’ve scraped their velvet.

“Then you gotta watch out. Rutting deer are bad enough, but when the flying reindeer go at it, it’s dangerous for the aircraft. We took to tethering ‘em just before they take off.

“But there was one year, ’01, Vixen was still in velvet and I had a bad run of Barbies in the shop…”

He raised an eyebrow.

“Yeah, you know, the Somali elves had just come on board and they didn’t know metric from English, and if you think Barbie’s proportions were unrealistic, that run was just plain science fiction. Anyway I just didn’t send the elves out to tether ‘em quick enough and before you knew it, Vixen was off. You know how those polar air currents are. Well, he went chasing the does outside of Atqisut Pass. I had to harness up an empty sleigh to go looking for him, and he was darned hard to catch when I got there. Good for me he was closing in on a bunch of estrus females when some Inuit opened fire and he lit out of there just as we were flying in.

“That’s the year I put GPS tracking onto their collars.”

Dear Readers: This is my first attempt at a humorous post. Please let me know what you think.